Founded in 1509, Brasenose College has a long and interesting history. These pages provide a brief introduction to the subject, detailing the history of its people and buildings and its customs and traditions. You will even find out where the name Brasenose comes from.

Before the foundation of Brasenose College part of the site was occupied by Brasenose Hall, one of the mediaeval Oxford institutions which began as lodging houses and gradually became more formal places of learning. The transformation of Brasenose Hall into Brasenose College was so smooth that it is difficult to give an exact date to the change.

A quarry in Headington was leased to provide stone for the new buildings on 19 June 1509 and this is the year which Brasenose keeps as its foundation. The royal Charter which established the body of Principal and Fellows is dated 15 January 1511/12. It established a College to be called 'The King's Hall and College of Brasenose' (in this sense Brasenose Hall still exists) for the study of sophistry, logic, philosophy and, above all, theology.

William Smyth

William Smyth

The founders of Brasenose College were Sir Richard Sutton, a lawyer, and William Smyth, Bishop of Lincoln. Both were from the north west and the College has retained strong links with Cheshire and Lancashire throughout its history. The Bishop provided for the expenses of the building and the lawyer acquired the property for the site.

There may not have been any undergraduates at all in the beginning, but at the end of the first hundred years there were 28 fellows and 87 undergraduates. Three of the early fellows gained notoriety, at least locally. One of them, William Eley, was at the execution of Thomas Cranmer in 1556, and is recorded as having disputed with him whilst he was actually burning at the stake. Another, named William Sutton, kept the wife of a Chipping Norton tradesman in a love nest, leading to an open fight with the constables of the town. We do not know what Roland Messenger, the very first Bursar, did, but each new fellow had to swear not to admit him to the College for more than one day; new fellows continued to swear this for over three hundred years.

During the first half of the seventeenth century Brasenose suffered recurring financial problems and by the 1640s the College was very poor and deeply in debt, owing £1,400 to tradesmen. These problems had not been solved when the Civil War began and Charles I made Oxford his headquarters. The city became an armed camp and academic life more or less ceased. Although Brasenose had hitherto had a Puritan reputation it joined the other colleges in supporting the king, giving up most of the silver for the war effort. When the Parliamentary authorities finally took over the University the Principal of Brasenose, Samuel Radcliffe, was one of those who refused to recognize their authority. He ignored orders expelling him from his position and remained defiant to the end, dying in the Principal's Lodgings six months later.

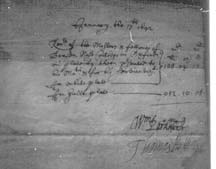

Receipt for College Silver sacrificed for the King

Receipt for College Silver sacrificed for the King

The eighteenth century was the period of the drunken Oxford undergraduate and the prosperous Brasenose fellow. Most of Oxford was Jacobite in sympathy, supporting the ousted royal line of James II after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, and Brasenose was no exception, having a strongly Jacobite Principal between 1710 and 1745 in Robert Shippen. He was described as 'a worldly man, having no small stock of confidence and nothing of letters, having wheedled himself into the affections of the great part of the College who expected to live easy under him without prosecution of studies'.

By this time the College had the reputation of being one of the wealthiest in Oxford and it had become the college of the country gentry, a place where the sons of gentlemen got a modicum of education and did a great deal of horse racing and fox hunting. However, the wealth was unfairly divided. From early days part of the revenue from the granting of leases by the College had been divided between the Principal and the six senior fellows, resulting in many complaints by the junior fellows, who could barely scratch a living. Of course the solution was for the juniors to reform the position when they became seniors, but somehow when they were promoted they seemed to lose their sense of the iniquity of the system. By the eighteenth century disputes between junior and senior fellows were the principal feature of College politics, hardly surprising when the senior fellows were earning five times as much as the juniors. The gap was to widen still further before the mid nineteenth century parliamentary reforms of the University.

Brasenose VIII February 1900

Brasenose VIII February 1900

Before the nineteenth century organized games were not usual for undergraduates; indeed some were actively forbidden. The growth of sport in Oxford was mostly due to the influence of the public schools. Rowing came first, followed by cricket. Brasenose was an early leader in Oxford sport and in the nineteenth century it acquired a great sporting reputation, rowing head of the river for many years and at one stage providing no fewer than eight members of the University cricket team. The greatest change in the history of the College took place in 1971, when the statutes were changed to allow the admission of women. The first woman lecturer was appointed in 1972 and the first women undergraduates arrived in 1974.